What AI is Actually Changing (It’s Not What You Think)

I’m going to start with two admissions. Firstly, I can’t remember my partner’s mobile number. Not perhaps the most drastic admission - but I grew up with landlines, knowing necessary numbers off the top of the hat. Now, I can’t make it stick the same way. This isn’t about getting older - it’s about something we’re all doing without noticing.

Secondly - and related, as you’ll see - my stance on AI has shifted. A year ago, I was sceptical. Now? Differently so. Not because AI has suddenly become perfect or harmless, but because I've realised the conversation we're having about it is missing something crucial.

We're so focused on what AI can do that we're not paying enough attention to what it's doing to us. And I don't mean this in the apocalyptic, Terminator sense. I mean it in a quieter, perhaps more insidious way: the erosion of cognitive capacities we might not miss until they're gone.

The Phone Number Problem

My now-dodgy memory of phone numbers isn't just about me getting older or lazier. It's about outsourcing memory to technology. Research by Andy Clarke and others has shown that when we adopt new technology, our brain structures change, often within about a year. We stop using the neural pathways we no longer need, and they atrophy. It's not unlike a muscle that stops being exercised.

The phone number thing feels trivial until you need to use someone else's phone in an emergency and realise you can't actually contact anyone. Then it becomes rather less trivial.

The Scaffolding We Lean On

Clarke talks about our use of tools as "scaffolding", external structures we use to support thinking - and external ones replacing processes that we used to have internally. Calculators replaced slide rules and mental arithmetic. GPS is replacing our sense of direction and ability to read maps. Smartphones replaced our need to remember... well, almost anything.

Each time we adopt one of these tools, we make a trade. We gain convenience and capability in some areas whilst losing capacity in others. The question isn't whether this trade is happening, it objectively is. The question is: are we conscious about which trades we're making?

With AI, particularly large language models, we're now outsourcing not just memory and calculation, but potentially something more fundamental: the process of thinking itself.

What We're Trading Away

When you ask ChatGPT or Claude to write something from scratch, you're not just getting help with a task, you're skipping several cognitive processes that might actually matter:

The struggle of articulation: That frustrating period when you're trying to work out exactly what you want to say forces you to clarify your own thinking. When AI generates text instantly, you bypass that clarification process entirely.

The discipline of structure: Working out how to organise an argument or narrative requires you to understand the relationships between ideas. AI can give you a structure, but do you really understand why that structure works?

The craft of revision: The difference between a first draft and a final version isn't just polish, it's the thinking you do whilst recognising what doesn't work and why. If AI generates something "pretty good" on the first attempt, do you have the discernment to know what "excellent" looks like?

I've noticed this in my own work. I can generate parts of proposals or reports through Claude and think, "Yeah, that's... that's pretty good." But then there's this nagging voice: am I settling? Have I lost some of the discernment I used to have about what constitutes genuinely good writing versus merely adequate writing?

The Word Recall Question

There's something more immediate happening too that I’ve noticed: word recall seems harder. Is it age? Possibly. But there's a suspicion that relying on AI to articulate things means we're not exercising that particular cognitive muscle as much.

It's subtle. You're writing an email response, and formulating a nuanced reply with proper context and tone feels harder than it should. So you ask AI to draft it. It works. You tweak it a bit. Job done. But did you just make it slightly harder to write that email yourself next time?

The research on neuroplasticity suggests yes. When we stop using certain neural pathways regularly, they become less efficient. The more we outsource articulation to AI, the less practised we become at articulating things ourselves.

This matters particularly for tasks that require nuance, context, and tone - exactly the things that make professional communication effective. You can get AI to draft an email, but the version you might have written after struggling through it yourself could have been more authentically you, more attuned to the specific relationship and situation. And you would have had a deeper, more authentic, somatic sense of what you were saying. It would stick with you. (There’s a movement in some universities to ban laptops for note-taking in lectures. The evidence is showing that writing notes helps integrate the material, improving the ability to apply it and recall it.)

The Simplicity Trap

There's another issue with current AI systems: they tend toward simplified answers. Eighteen months ago, if you asked an image generator to show you a doctor, you'd get a man in every image. That's been corrected (mostly), but the underlying problem remains: AI systems are trained on existing patterns, which means they reinforce existing biases and simplifications.

In text generation, this manifests as AI giving you definitive answers when nuanced ones would be more appropriate. Ask it how to fix an organisational problem, and you'll likely get a clear, structured response that makes the solution seem straightforward. But complex problems - particularly in human systems - rarely have straightforward solutions.

If you're using AI extensively, you risk training yourself to expect simple answers. The world becomes more binary: problems have solutions, questions have answers, complexity can be resolved with a clear action plan. Except that's not how organisations, people, or most interesting problems actually work.

The Difference Between Getting And Knowing

There's a related trap I fell into with academic papers. I've always found them hard going - the language is drier, more formal, more specialised than I'm used to. So for a while, I started dropping them into Claude and asking: "Give me the key points and things I should think about, in plain English, as though you were talking to a smart friend."

It worked brilliantly. I got clear, accessible summaries that were far easier to read than the originals.

But here's what I noticed: they didn't stick. I'd read the summary, nod along, and three weeks later have only the vaguest sense of what the paper had said. The information had passed through without lodging anywhere and without changing how I thought - which was the main point of the exercise.

So I've changed how I use it. Now it's less "summarise this for me" and more "have a conversation with me about this - help me position it against what I already know, challenge where it conflicts with my assumptions, and work through the nuances with me."

The difference isn't just about retention. It's the difference between being given an answer and actually knowing something. The first is faster. The second is mine.

The Co-Evolution Question

Human beings and our technologies co-evolve. We're not separate from our tools; we're shaped by them even as we shape them. Which means you can't fully understand AI's implications from the outside - by reading about it, or watching others use it, or deciding in advance what you think. The only way to grasp what it's actually doing to cognition is to use it yourself, pay attention, and work it out as you go.

That's partly why I'm sharing my own experiments here. Not because I've figured it out, but because figuring it out requires engagement. The question isn't whether AI will change us - it already is. The questions are:

What cognitive capacities are we willing to trade away? Memory? Calculation? Fair enough - we made those trades decades ago. But what about articulation? Reasoning? Discernment? Creativity? Where do we draw the line?

What new capacities do we need to develop? If we're outsourcing certain types of thinking, what should we be getting better at instead? Perhaps it's the ability to prompt effectively, to direct AI toward useful outputs. Perhaps it's developing stronger evaluative skills - the ability to recognise good thinking from mediocre thinking. Perhaps it's something we haven't even identified yet.

How do we maintain critical distance? When a tool becomes indispensable, we stop questioning it. How do we use AI extensively whilst maintaining healthy scepticism about its outputs and awareness of what we're losing?

The Thought Partner Approach

I've settled (for now) on thinking of AI as a thought partner - but one that requires active management. This means being deliberate about which parts of the thinking process to outsource and which to keep.

For my newsletter, I'll use Claude to map out structure and create a rough content schedule. But I won't let it write the first draft. I write that myself, then use AI to identify what's unclear or where I'm using too much jargon. Then I rewrite it - I don't let the AI rewrite it for me.

For emails where I need to get across complex context and nuance, I might ask for a draft. But I'll ask it to start by asking me questions it needs answered to write a good response. Then I take that draft and make it properly mine. (As an aside - the exercise of having it ask me questions often helps my own clarity about the purpose and content of the email.)

The principle is: use AI to accelerate parts of the process, but don't skip the parts that build your own capabilities or are your unique strength.

The Skills We Should Develop

If we're going to use AI extensively (and let's face it,most of us are), we need to deliberately develop complementary skills:

Discernment: The ability to evaluate quality, to know when something is truly good versus merely adequate. AI can generate competent work quickly, but can you tell the difference between competent and excellent? Between accurate and slightly off?

Prompting: How to direct AI effectively, give it the right context, ask the right questions. This is becoming a skill in its own right, though perhaps a temporary one until interfaces improve.

Integration: Taking AI-generated content and making it genuinely yours - not just tweaking a few words, but ensuring it reflects your actual thinking and voice.

Meta-cognition: Awareness of your own thinking process. Which parts do you actually need to do yourself to maintain the skill? Which parts can be safely outsourced? What parts do you need to develop?

These aren't skills that develop accidentally. They require conscious effort and practice.

The Output Trap

A colleague recently shared a post about a professor catching students using AI to write essays. The tone was slightly triumphant - gotcha.

But something about it nagged at me. The professor's frustration assumes the essay is what proves thinking happened. He's asking students to produce a thing, not do a process - and then being surprised when they optimise for the thing.

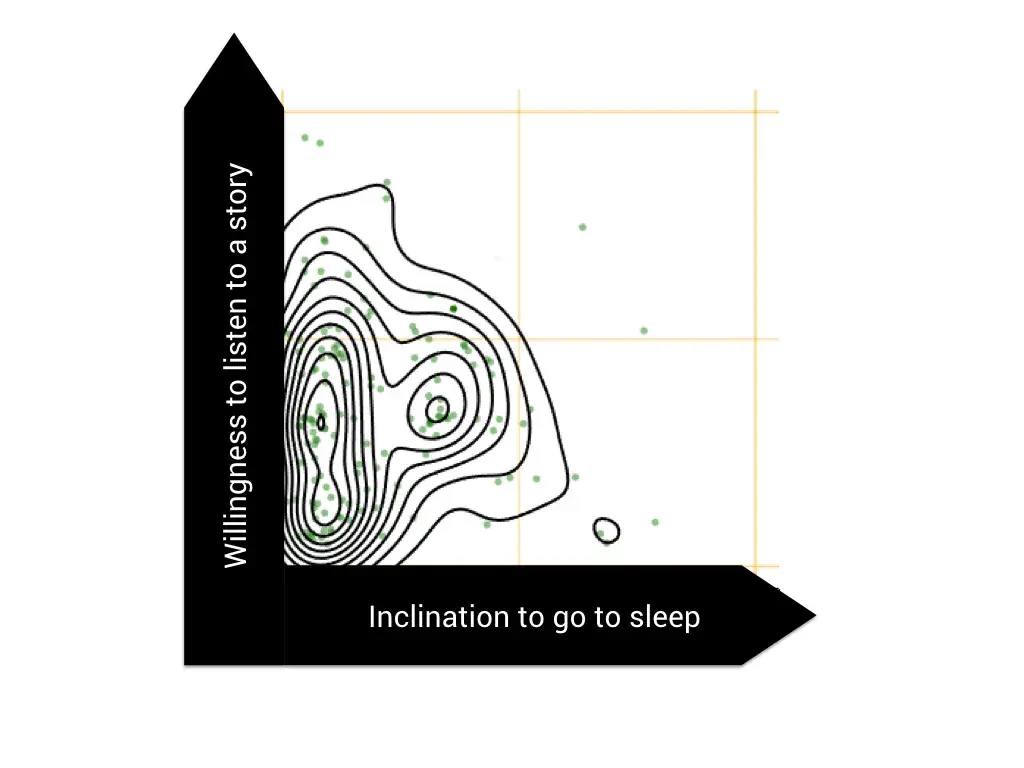

I see this pattern elsewhere. I work with leaders on polarity maps - a tool for navigating tensions that can't be "solved," only managed. Early on, I noticed people treating the map itself as the deliverable. Get the quadrants filled in, job done.

I've learned to emphasise that the map isn't the point. The thinking you do while creating it is the point. The map is just a residue of that thinking - useful as a reference, but not where the value lives.

This is where AI gets interesting rather than threatening. An LLM can produce a perfectly adequate polarity map in seconds. But it can also sit alongside you while you wrestle with the tensions yourself - pushing your thinking, challenging your assumptions, asking awkward questions. One gives you an output. The other develops your capacity.

The question for education isn't "how do we stop students using AI?" It's "have we been assessing the right thing all along?" If we've been treating outputs as proxies for thinking, maybe AI is just revealing that the proxy was always a bit broken.

I've recently been working with a client on exactly this - developing prompts for their leaders to use with the company's approved AI. The shift was from "help me write this email" or "make me more productive" to "help me think through this issue using different frames" or "challenge my assumptions about this decision before I commit." Same tool, completely different cognitive relationship with it.

The Constraints We Might Need

Perhaps we need to start thinking about constraints. Not prohibitions exactly, but deliberate boundaries around AI use that help maintain important capabilities.

For my newsletter, my constraint is: AI doesn't write the first draft. That's my thinking process, and I need to maintain it.

For complex client work, my constraint might be: AI can help me structure my thinking, but I need to do the hard cognitive work of making sense of the problem myself first.

For others, constraints might look different. A student might commit to always writing their own first draft before asking AI for feedback. A manager might use AI for initial email drafts but insist on rewriting the crucial bits themselves.

The point isn't that there's one right approach. The point is being conscious about the trade-offs and making deliberate choices rather than drifting into complete dependence.

The Unintended Consequences We Can't Predict

Here's the uncomfortable truth: we don't know what we're trading away until it's gone. The full impact of any technology only becomes clear years or decades after adoption.

Nobody anticipated that smartphones would fundamentally change how we experience boredom, or that social media would reshape political discourse, or that GPS would affect our spatial reasoning. These were unintended consequences that only became apparent over time.

AI will have its own set of unintended consequences. Some we might guess at - the erosion of certain cognitive skills, the flattening of thinking into simplified patterns, the loss of comfort with uncertainty and complexity. But others will surprise us entirely.

The question is whether we're watching for them. Are we monitoring not just what AI enables but what it might be costing us? Are we paying attention to which cognitive muscles are atrophying? Are we noticing when we settle for "good enough" outputs because we've lost the ability to recognise what "excellent" looks like?

Moving Forward Thoughtfully

I'm not arguing for rejecting AI. I use it. I'll continue using it. But I'm trying to use it thoughtfully, with awareness of what I'm trading.

This means:

Regular self-assessment: Periodically checking - am I still able to do this myself? Has my word recall actually gotten worse? Can I still write a complex email without AI assistance?

Deliberate practice: Consciously exercising cognitive skills that I want to maintain, even when AI could do them faster.

Healthy scepticism: Questioning AI outputs, not accepting them uncritically even when they seem good.

Watching for atrophy: Noticing when tasks that used to be straightforward start feeling harder, and considering whether AI use might be contributing.

Accepting complexity: Resisting thet temptation to settle for simplified answers when nuanced ones are more appropriate.

The conversation around AI tends toward extremes - either enthusiastic adoption or fearful rejection. But the more interesting space is the middle ground: thoughtful, aware use that acknowledges both benefits and costs.

We're going to use AI. The technology is too useful to ignore. But that doesn't mean we have to use it unconsciously. We can make deliberate choices about which cognitive trade-offs are worth making and which aren't.

The key is keeping watch on ourselves - noticing what we're gaining and what we're losing, and being willing to adjust course when the balance tips wrong. Because the unintended consequences of AI won't announce themselves. They'll arrive quietly, one small trade-off at a time, until we look up one day and realise we've outsourced more of our thinking than we meant to.

The question is: will we notice before the capacity to notice has atrophied too?

Image Source: Canva

- Narrative (100)

- Organisational culture (97)

- Communications (93)

- Complexity (79)

- SenseMaker (78)

- Changing organisations (42)

- Cognitive Edge (37)

- Narrate news (35)

- narrative research (34)

- Cognitive science (25)

- Tools and techniques (25)

- Conference references (24)

- Recommendations (20)

- datespecific (20)

- Leadership (18)

- Employee engagement (16)

- Storytelling (15)

- Culture (13)

- Events (11)

- UNDP (11)

- Cynefin (10)

- hints and tips (10)

- internal communications (8)

- Engagement (7)

- culture change (7)

- Knowledge (6)

- M&E (6)

- Stories (6)

- customer insight (6)

- tony quinlan (6)

- Branding (5)

- Changing organisations (5)

- Children of the World (4)

- Dave Snowden (4)

- case study (4)

- corporate culture (4)

- Courses (3)

- GirlHub (3)

- Medinge (3)

- Travel (3)

- anecdote circles (3)

- development (3)

- knowledge management (3)

- merger (3)

- micro-narratives (3)

- monitoring and evaluation (3)

- presentations (3)

- Attitudes (2)

- BRAC (2)

- Bratislava (2)

- Egypt (2)

- ILO (2)

- Narattive research (2)

- Roma (2)

- Uncategorized (2)

- VECO (2)

- citizen engagement (2)

- corporate values (2)

- counter-terrorism (2)

- customer satisfaction (2)

- diversity (2)

- governance (2)

- impact measurement (2)

- innovation (2)

- masterclass (2)

- melcrum (2)

- monitoring (2)

- narrate (2)

- navigating complexity (2)

- organisation culture (2)

- organisational storytelling (2)

- research (2)

- sensemaker case study (2)

- sensemaking (2)

- social networks (2)

- speaker (2)

- strategic narrative (2)

- strategy (2)

- workshops (2)

- 2012 Olympics (1)

- Adam Curtis (1)

- Allders of Sutton (1)

- CASE (1)

- Cabinets and the Bomb (1)

- Central Library (1)

- Chernobyl (1)

- Christmas (1)

- Complexity Training (1)

- Disaster relief (1)

- Duncan Green (1)

- ESRC (1)

- Employee surveys (1)

- European commission (1)

- Fail-safe (1)

- Financial Times anecdote circles SenseMaker (1)

- FlashForward (1)

- Fragments of Impact (1)

- Future Backwards (1)

- GRU (1)

- Girl Research Unit (1)

- House of Lords (1)

- Huffington Post (1)

- IQPC (1)

- Jordan (1)

- Joshua Cooper Ramo (1)

- KM (1)

- KMUK2010 (1)

- Kharian and Box (1)

- LFI (1)

- LGComms (1)

- Lant Pritchett (1)

- Learning From Incidents (1)

- Lords Speaker lecture (1)

- MLF (1)

- MandE (1)

- Montenegro (1)

- Mosaic (1)

- NHS (1)

- ODI (1)

- OTI (1)

- Owen Barder (1)

- PR (1)

- Peter Hennessy (1)

- Pfizer (1)

- Protected Areas (1)

- Rwanda (1)

- SenseMaker® collector ipad app (1)

- Serbia (1)

- Sir Michael Quinlan (1)

- Slides (1)

- Speaking (1)

- Sutton (1)

- TheStory (1)

- UK justice (1)

- USS vincennes (1)

- United Nations Development Programme (1)

- Washington storytelling (1)

- acquisition (1)

- adaptive management (1)

- afghanistan (1)

- aid and development (1)

- al-qaeda (1)

- algeria (1)

- all in the mind (1)

- anthropology (1)

- applications (1)

- back-story (1)

- better for less (1)

- change communications (1)

- change management (1)

- citizen experts (1)

- communication (1)

- communications research (1)

- complaints (1)

- complex adaptive systems (1)

- complex probes (1)

- conference (1)

- conferences (1)

- conspiracy theories (1)

- consultation (1)

- content management (1)

- counter narratives (1)

- counter-insurgency (1)

- counter-narrative (1)

- creativity (1)

- customer research (1)

- deresiewicz (1)

- deterrence (1)

- dissent (1)

- downloads (1)

- education (1)

- employee (1)

- ethical audit (1)

- ethics (1)

- evaluation (1)

- facilitation (1)

- fast company (1)

- feedback loops (1)

- financial services (1)

- financial times (1)

- four yorkshiremen (1)

- gary klein (1)

- georgia (1)

- girl effect (1)

- girleffect (1)

- giving voice (1)

- globalgiving (1)

- harnessing complexity (1)

- impact evaluation (1)

- impact measures (1)

- information overload (1)

- informatology (1)

- innovative communications (1)

- john kay (1)

- justice (1)

- kcuk (1)

- keynote (1)

- leadership recession communication (1)

- learning (1)

- libraries (1)

- likert scale (1)

- lucifer effect (1)

- marketing (1)

- minimum level of failure (1)

- narrative capture (1)

- narrative sensemaker internal communications engag (1)

- natasha mitchell (1)

- new york times (1)

- newsletter (1)

- obliquity (1)

- organisation (1)

- organisational development (1)

- organisational memory (1)

- organisational narrative (1)

- patterns (1)

- pilot projects (1)

- placement (1)

- policy-making (1)

- population research (1)

- presentation (1)

- protocols of the elders of zion. (1)

- public policy (1)

- public relations (1)

- qualitative research (1)

- quangos (1)

- relations (1)

- reputation management (1)

- resilience (1)

- revenge (1)

- ritual dissent (1)

- road signs (1)

- safe-fail (1)

- safe-to-fail experiments (1)

- sales improvement (1)

- satisfaction (1)

- scaling (1)

- seminar (1)

- seth godin (1)

- social coherence (1)

- social cohesion (1)

- solitude (1)

- stakeholder understanding (1)

- strategic communications management (1)

- suggestion schemes (1)

- surveys (1)

- survivorship bias (1)

- targets (1)

- tbilisi (1)

- the future backwards (1)

- tipping point (1)

- training (1)

- twitter (1)

- upskilling (1)

- values (1)

- video (1)

- voices (1)

- weak links (1)

- zeno's paradox (1)

- January 2026 (1)

- December 2025 (1)

- October 2025 (1)

- September 2025 (1)

- August 2025 (3)

- July 2025 (2)

- February 2025 (3)

- January 2025 (1)

- November 2024 (1)

- October 2024 (1)

- September 2024 (2)

- March 2020 (1)

- November 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- May 2019 (2)

- April 2019 (1)

- November 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (2)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (1)

- November 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (2)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- February 2016 (1)

- January 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (3)

- May 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (2)

- February 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (3)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (2)

- June 2014 (6)

- May 2014 (3)

- April 2014 (3)

- March 2014 (5)

- January 2014 (4)

- December 2013 (2)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (1)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (1)

- January 2013 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- October 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (3)

- November 2011 (3)

- August 2011 (1)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (4)

- April 2011 (3)

- March 2011 (4)

- February 2011 (8)

- January 2011 (8)

- December 2010 (2)

- November 2010 (5)

- October 2010 (8)

- September 2010 (5)

- August 2010 (2)

- June 2010 (1)

- April 2010 (2)

- January 2010 (1)

- December 2009 (2)

- November 2009 (4)

- October 2009 (1)

- January 2009 (1)

- July 2008 (4)

- June 2008 (1)

- March 2008 (2)

- January 2008 (3)

- November 2007 (4)

- October 2007 (1)

- September 2007 (1)

- August 2007 (4)

- May 2007 (3)

- March 2007 (1)

- February 2007 (6)

- January 2007 (3)

- November 2006 (7)

- October 2006 (8)

- September 2006 (2)

- August 2006 (5)

- July 2006 (13)

Subscribe by email

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

Mrs Trellis, red-shirts and savings - the limits of text analysis

Making sense of thousands of stories, suggestions or complaints