“Well we know where we’re going, but we don’t know where we’ve been.”

David Byrne wasn't writing about organisational change, but he might as well have been.

Every organisation has an invisible architecture of understanding - the accumulated stories and patterns that explain to people "how things really work around here". Your change programme is about to collide with it.

When change fails, post-mortems focus on implementation. Wrong question. The more useful one: did anyone understand how people made sense of where they were before trying to move them somewhere new?

The Pattern Matching Problem

Human beings don't process information in the neat, logical way that change programmes assume. As research by Gary Klein and others into naturalised decision-making has shown, we don't methodically analyse data and weigh options. Instead, we pattern match.

We take in fragments of information and unconsciously compare them against the patterns already stored in our minds - patterns built from our own experiences and, crucially, from the stories we've absorbed about how our organisation works. When we encounter a new situation, we're asking: "What does this remind me of? What pattern does this fit?"

This has profound implications for organisational change. When you announce a new strategy or initiative, people aren't hearing your carefully crafted message in isolation. They're matching it against their existing patterns: "This sounds like that restructure three years ago that went nowhere," or "This reminds me of what happened when Sarah tried to change how we work with customers."

The stories circulating around the organisation - whether shared at the coffee machine, during lunch breaks, or in those knowing glances during meetings - create the patterns people use to interpret everything you're trying to do.

The Danger Of Incomplete Narratives

Leaders often make a critical error when communicating change: they tell success stories whilst omitting the struggles, setbacks, and complications that inevitably occurred. The intention is understandable - inspire people, create momentum, paint an optimistic picture. But the result is often counterproductive.

When you share only the polished, triumphant version of how change happened, you're providing an incomplete pattern. Teams then go out to implement the change and immediately hit obstacles that weren't mentioned in the official narrative. Rather than seeing these difficulties as normal, they interpret them as signs of failure: "Sarah said it was plain sailing, but it's really challenging for us. Something must be wrong."

This false narrative doesn't just demotivate people - it actively undermines their ability to navigate complexity. By withholding the full story, including the messy, difficult bits, you deprive people of the patterns they need to recognise that struggle is part of the process, not evidence of incompetence.

I've chaired enough communications conferences to watch this pattern repeat. A speaker presents their change programme - eighteen months, successful rollout, engagement transformed. The audience reaction is always the same: "You don't understand, we couldn't do that in our organisation." They're not wrong, but not for the reasons they think. What they're reacting to is an incomplete pattern - the version that omits the false starts, the resistance, the moments it nearly failed. Without those, the story isn't transferable. It's just a highlight reel that makes everyone else feel inadequate.

But there's a more troubling version of this: leaders who believe their own incomplete narrative. I see it constantly on LinkedIn - a rebrand or new CEO announced with "we're starting with a clean sheet of paper." As if organisational memory works like that.

I once met a head of communications for a newly reorganised local authority. "It's great," he told me. "We're now 'Central Bedfordshire' - a completely fresh beginning with our citizens." I pointed out that most residents probably experienced the change from "Mid-Bedfordshire" as barely cosmetic. He couldn't see it. For him, the rename was the reset. The citizens' twenty years of stories about how the council actually works? Still running, unchanged, underneath the new letterhead.

The Hidden Stories That Shape Reality

Organisations operate on multiple levels of narrative simultaneously. There's the official story - the one in the annual report, the CEO's presentations, the values on the wall. But there are countless other stories running in parallel: the myths about who gets promoted and why, the legends about past successes and failures, the cautionary tales about what happens when you challenge the status quo.

These unofficial narratives often have far more influence on behaviour than any amount of official communication. They tell people:

- What's actually rewarded versus what's officially praised

- Where the real power lies in the organisation

- What risks are acceptable to take

- Who fits in and who doesn't

- What the boundaries of acceptable behaviour truly are

When your culture tells people that despite the official values of innovation and risk-taking, what actually gets you ahead is keeping your head down and hitting your numbers, that's the pattern people will follow. The stories people tell each other shape reality far more effectively than the stories leaders tell to them.

Shared Language Versus Shared Meaning

Internal communications teams frequently strive for alignment - getting everyone using the same language, talking about innovation, customer-centricity, agility, and other organisational priorities. This feels productive. It looks like progress. But it can be dangerously misleading.

Using the same words doesn't mean people share the same understanding. When everyone talks about "innovation," they might mean entirely different things - from incremental process improvements to radical product development. These differences remain hidden beneath the common vocabulary, only emerging later as conflicts, misunderstandings, or failed initiatives.

What organisations actually need isn't shared language, but shared meaning. This is where stories become essential. Abstract concepts like "customer focus" or "accountability" mean little until they're grounded in specific examples: "Remember when James stayed late to help that customer sort out their issue?" or "That time the team decided to scrap three months of work because it wasn't right for clients."

Stories provide the concrete detail that allows people to triangulate what abstract values actually mean in practice. More importantly, they allow for productive differences meaning that people can use the same stories to reach slightly different understandings, whilst still maintaining enough shared meaning to collaborate effectively.

The Technique: Listening First

Before attempting to shift an organisational culture or implement change, leaders need to understand the existing landscape of stories and sense-making. This isn't complicated, but it does require a fundamental shift in approach: from telling to listening.

The technique is straightforward - create spaces where people can share their experiences without being funnelled into predetermined categories. This might be through:

Anecdote circles: Gathering small groups and simply asking: "Tell me about a time when you've seen really good leadership here," or "What frustrated you this week? What happened?" These sessions work like competitive storytelling - one person's example triggers another's memory, and soon you're gathering a rich, contextual understanding of what work actually feels like.

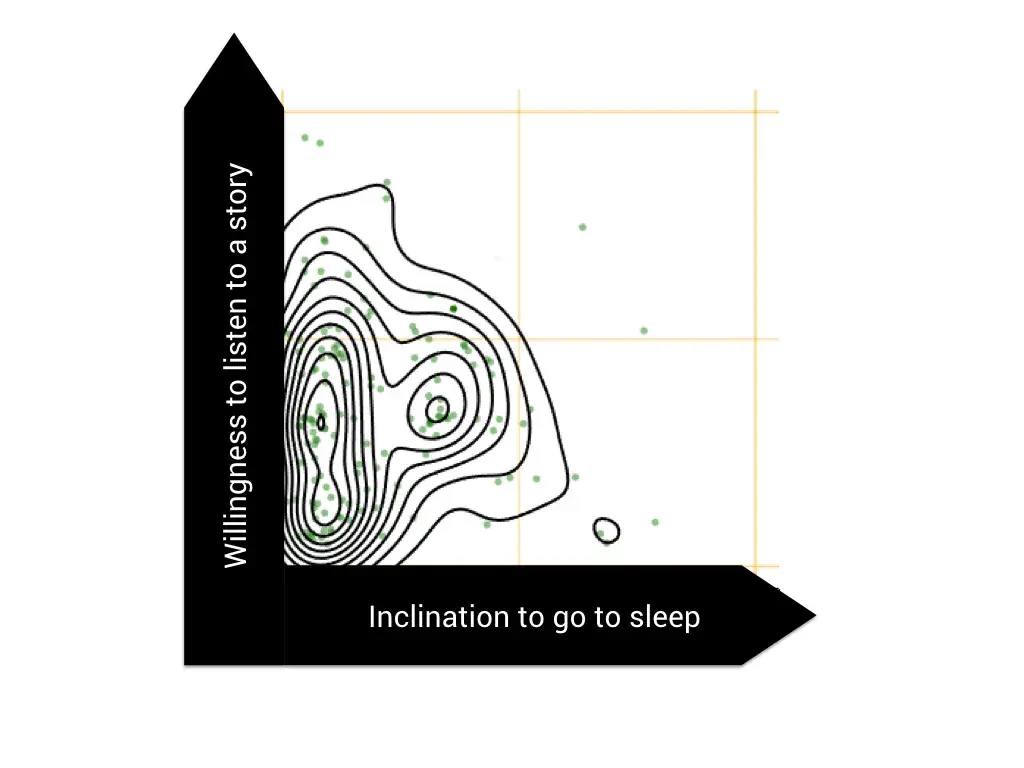

Narrative collection at scale: For larger organisations, tools like SenseMaker® allow you to gather hundreds or thousands of experiences, asking people to interpret their own stories through carefully designed frameworks. This reveals patterns in how people make sense of their work.

Strategic listening posts: Rather than formal surveys, create ongoing ways to hear what's happening - whether that's leadership spending time in different parts of the organisation, creating anonymous channels for sharing examples, or training managers to actively seek out stories rather than just opinions.

What you're listening for isn't just content, but patterns: What stories get repeated? What examples are people using to makkeynote speakerse sense of their situation? Where are the disconnects between official narratives and lived experience?

Finding The Future In The Present

William Gibson famously observed: "The future is already here. It's just really badly distributed." This is profoundly true for organisations.

The culture you want probably already exists somewhere in your organisation - perhaps in one team, one location, one group of people who've found a way to work that embodies your aspirations. Similarly, the problematic behaviours you're trying to eliminate are already present, perhaps disguised or rationalised but nonetheless real.

Rather than trying to impose a new culture from above, the task becomes one of pattern recognition and amplification.This is what it means to work with organisations as complex systems - you can't control culture directly, but you can shift the conditions that shape it. Where are examples of the behaviours and ways of working you want more of? Where are examples of what you want less of? By spotlighting these existing examples, you help people triangulate towards the desired culture.

The phrase that captures this approach: "What might we do to create more examples like these and fewer like those?"

This isn't about mandating behaviour or issuing directives. It's about helping people see patterns they're already living with and making conscious choices about which patterns to strengthen and which to weaken.

Making Change Stick

Traditional change management often fails because it treats people as empty vessels to be filled with new information and processes. But people already have rich, complex understandings of their organisational reality. Successful change requires engaging with these existing mental models, not overwriting them.

This means:

Starting with diagnosis, not prescription: Before announcing what needs to change, understand how people currently make sense of the situation. What patterns are they using? What stories are they telling?

Sharing the struggles, not just the successes: When communicating about change, include the difficulties and setbacks. Give people realistic patterns to match against when they encounter obstacles.

Creating space for meaning-making: Rather than just broadcasting messages, create opportunities for people to share their experiences, compare notes, and collectively make sense of what's happening.

Using examples, not just abstracts: Instead of talking about values and principles in the abstract, constantly refer to specific examples - both positive and negative - that illustrate what you mean.

Monitoring the narrative landscape: Culture isn't static. Continuously listen for how stories are evolving, what new patterns are emerging, and whether the changes you're seeing are the ones you intended.

So What?

You cannot successfully move an organisation from where it is to where you want it to be unless you first understand how people make sense of where they are now. This isn't a philosophical nicety - it's the difference between change that sticks and change that becomes another cautionary tale.

The stories people tell themselves and each other create the patterns they use to interpret everything else. These patterns determine which initiatives gain traction and which fade away, which leaders are trusted and which aren't, which changes are embraced and which are resisted.

Before embarking on your next change programme, ask yourself: Do I understand the stories people are telling about how we got here? Have I listened deeply enough to understand their reality?

If the answer is no, you know where you're going. You just don't know where you've been.

And Talking Heads had a name for that road.

Image Source: Canva

- Narrative (100)

- Organisational culture (98)

- Communications (93)

- Complexity (79)

- SenseMaker (78)

- Changing organisations (42)

- Cognitive Edge (37)

- Narrate news (35)

- narrative research (34)

- Cognitive science (25)

- Tools and techniques (25)

- Conference references (24)

- Recommendations (20)

- datespecific (20)

- Leadership (18)

- Employee engagement (16)

- Storytelling (15)

- Culture (13)

- Events (11)

- UNDP (11)

- Cynefin (10)

- hints and tips (10)

- internal communications (8)

- Engagement (7)

- culture change (7)

- Knowledge (6)

- M&E (6)

- Stories (6)

- customer insight (6)

- tony quinlan (6)

- Branding (5)

- Changing organisations (5)

- Children of the World (4)

- Dave Snowden (4)

- case study (4)

- corporate culture (4)

- Courses (3)

- GirlHub (3)

- Medinge (3)

- Travel (3)

- anecdote circles (3)

- development (3)

- knowledge management (3)

- merger (3)

- micro-narratives (3)

- monitoring and evaluation (3)

- organisation culture (3)

- presentations (3)

- Attitudes (2)

- BRAC (2)

- Bratislava (2)

- Egypt (2)

- ILO (2)

- Narattive research (2)

- Roma (2)

- Uncategorized (2)

- VECO (2)

- citizen engagement (2)

- corporate values (2)

- counter-terrorism (2)

- customer satisfaction (2)

- diversity (2)

- governance (2)

- impact measurement (2)

- innovation (2)

- masterclass (2)

- melcrum (2)

- monitoring (2)

- narrate (2)

- navigating complexity (2)

- organisational storytelling (2)

- research (2)

- sensemaker case study (2)

- sensemaking (2)

- social networks (2)

- speaker (2)

- strategic narrative (2)

- strategy (2)

- workshops (2)

- 2012 Olympics (1)

- Adam Curtis (1)

- Allders of Sutton (1)

- Artificial Intelligence (1)

- CASE (1)

- Cabinets and the Bomb (1)

- Central Library (1)

- Chernobyl (1)

- Christmas (1)

- Complexity Training (1)

- Disaster relief (1)

- Duncan Green (1)

- ESRC (1)

- Employee surveys (1)

- European commission (1)

- Fail-safe (1)

- Financial Times anecdote circles SenseMaker (1)

- FlashForward (1)

- Fragments of Impact (1)

- Future Backwards (1)

- GRU (1)

- Girl Research Unit (1)

- House of Lords (1)

- Huffington Post (1)

- IQPC (1)

- Jordan (1)

- Joshua Cooper Ramo (1)

- KM (1)

- KMUK2010 (1)

- Kharian and Box (1)

- LFI (1)

- LGComms (1)

- Lant Pritchett (1)

- Learning From Incidents (1)

- Lords Speaker lecture (1)

- MLF (1)

- MandE (1)

- Montenegro (1)

- Mosaic (1)

- NHS (1)

- ODI (1)

- OTI (1)

- Owen Barder (1)

- PR (1)

- Peter Hennessy (1)

- Pfizer (1)

- Protected Areas (1)

- Rwanda (1)

- SenseMaker® collector ipad app (1)

- Serbia (1)

- Sir Michael Quinlan (1)

- Slides (1)

- Speaking (1)

- Sutton (1)

- TheStory (1)

- UK justice (1)

- USS vincennes (1)

- United Nations Development Programme (1)

- Washington storytelling (1)

- acquisition (1)

- adaptive management (1)

- afghanistan (1)

- aid and development (1)

- al-qaeda (1)

- algeria (1)

- all in the mind (1)

- anthropology (1)

- applications (1)

- back-story (1)

- better for less (1)

- change communications (1)

- change management (1)

- citizen experts (1)

- communication (1)

- communications research (1)

- complaints (1)

- complex adaptive systems (1)

- complex probes (1)

- conference (1)

- conferences (1)

- conspiracy theories (1)

- consultation (1)

- content management (1)

- counter narratives (1)

- counter-insurgency (1)

- counter-narrative (1)

- creativity (1)

- customer research (1)

- deresiewicz (1)

- deterrence (1)

- dissent (1)

- downloads (1)

- education (1)

- employee (1)

- ethical audit (1)

- ethics (1)

- evaluation (1)

- facilitation (1)

- fast company (1)

- feedback loops (1)

- financial services (1)

- financial times (1)

- four yorkshiremen (1)

- gary klein (1)

- georgia (1)

- girl effect (1)

- girleffect (1)

- giving voice (1)

- globalgiving (1)

- harnessing complexity (1)

- impact evaluation (1)

- impact measures (1)

- information overload (1)

- informatology (1)

- innovative communications (1)

- john kay (1)

- justice (1)

- kcuk (1)

- keynote (1)

- leadership recession communication (1)

- learning (1)

- libraries (1)

- likert scale (1)

- lucifer effect (1)

- marketing (1)

- minimum level of failure (1)

- narrative capture (1)

- narrative sensemaker internal communications engag (1)

- natasha mitchell (1)

- new york times (1)

- newsletter (1)

- obliquity (1)

- organisation (1)

- organisational development (1)

- organisational memory (1)

- organisational narrative (1)

- patterns (1)

- pilot projects (1)

- placement (1)

- policy-making (1)

- population research (1)

- presentation (1)

- protocols of the elders of zion. (1)

- public policy (1)

- public relations (1)

- qualitative research (1)

- quangos (1)

- relations (1)

- reputation management (1)

- resilience (1)

- revenge (1)

- ritual dissent (1)

- road signs (1)

- safe-fail (1)

- safe-to-fail experiments (1)

- sales improvement (1)

- satisfaction (1)

- scaling (1)

- seminar (1)

- seth godin (1)

- social coherence (1)

- social cohesion (1)

- solitude (1)

- stakeholder understanding (1)

- strategic communications management (1)

- suggestion schemes (1)

- surveys (1)

- survivorship bias (1)

- targets (1)

- tbilisi (1)

- the future backwards (1)

- tipping point (1)

- training (1)

- twitter (1)

- upskilling (1)

- values (1)

- video (1)

- voices (1)

- weak links (1)

- zeno's paradox (1)

- February 2026 (2)

- January 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (1)

- October 2025 (1)

- September 2025 (1)

- August 2025 (3)

- July 2025 (2)

- February 2025 (3)

- January 2025 (1)

- November 2024 (1)

- October 2024 (1)

- September 2024 (2)

- March 2020 (1)

- November 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- May 2019 (2)

- April 2019 (1)

- November 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (2)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (1)

- November 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (2)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- February 2016 (1)

- January 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (3)

- May 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (2)

- February 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (3)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (2)

- June 2014 (6)

- May 2014 (3)

- April 2014 (3)

- March 2014 (5)

- January 2014 (4)

- December 2013 (2)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (1)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (1)

- January 2013 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- October 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (3)

- November 2011 (3)

- August 2011 (1)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (4)

- April 2011 (3)

- March 2011 (4)

- February 2011 (8)

- January 2011 (8)

- December 2010 (2)

- November 2010 (5)

- October 2010 (8)

- September 2010 (5)

- August 2010 (2)

- June 2010 (1)

- April 2010 (2)

- January 2010 (1)

- December 2009 (2)

- November 2009 (4)

- October 2009 (1)

- January 2009 (1)

- July 2008 (4)

- June 2008 (1)

- March 2008 (2)

- January 2008 (3)

- November 2007 (4)

- October 2007 (1)

- September 2007 (1)

- August 2007 (4)

- May 2007 (3)

- March 2007 (1)

- February 2007 (6)

- January 2007 (3)

- November 2006 (7)

- October 2006 (8)

- September 2006 (2)

- August 2006 (5)

- July 2006 (13)

Subscribe by email

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

SenseMaker contours of narrative - how a culture might evolve, where a culture won't shift

Argh. When a helpful example is kept confidential